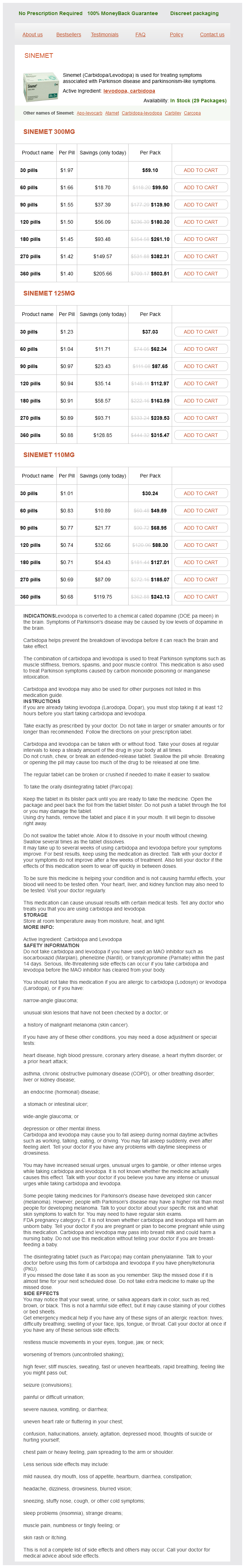

Sinemet

Sinemet 300mg

- 30 pills - $59.10

- 60 pills - $99.50

- 90 pills - $139.90

- 120 pills - $180.30

- 180 pills - $261.10

- 270 pills - $382.31

- 360 pills - $503.51

Sinemet 125mg

- 30 pills - $37.03

- 60 pills - $62.34

- 90 pills - $87.65

- 120 pills - $112.97

- 180 pills - $163.59

- 270 pills - $239.53

- 360 pills - $315.47

Sinemet 110mg

- 30 pills - $30.24

- 60 pills - $49.59

- 90 pills - $68.95

- 120 pills - $88.30

- 180 pills - $127.01

- 270 pills - $185.07

- 360 pills - $243.13

Place the patient in a supine position with the foot and ankle extending off the end of the stretcher medications you cant crush effective 110 mg sinemet. Alternatively, ask an assistant to elevate the leg or place pillows under the knee and foreleg. Wrap the ankle and foot with five to seven layers of Webril starting at the metatarsal heads and continuing around the ankle in a figure-of-eight configuration. Extend the Webril 5 to 7 cm above the malleoli and overlap each turn by 25% to 50% of its width. After the Webril is in place, wrap an elastic bandage around the foot and ankle in a similar fashion. Complaints of pain under this cast were incorrectly met with a phone call to suggest elevation and a call-in prescription for narcotics. Although the risk for ischemia is drastically reduced with splinting, Webril or elastic bandages can cause significant constriction. To reduce the likelihood of constriction occurring, do not pull the elastic bandage excessively tight. If the patient has a high-risk injury, cut the Webril lengthwise before the plaster is applied. Stress the importance of elevation, no weight bearing, and application of cold packs, and carefully review the signs and symptoms of vascular compromise with every patient. All patients whose injuries have the potential for significant swelling or loss of vascular integrity should receive followup care in the first 24 to 48 hours. Patients with splint-related discomfort must be reevaluated clinically and should not be treated with a telephone prescription for opioid analgesics. Their effects are additive, and this fact should be taken into account when applying a splint. For example, if 15 sheets of plaster are needed for strength in a particular splint, one should not increase the heat production further by using extra-fastdrying plaster or reusing warm dip water. To avoid plaster burns, use only 8 to 12 sheets of plaster when possible, use fresh dip water with a temperature near 24°C, and never wrap the extremity in a sheet or pillow during the setting process. The heat of drying may produce pain in patients with hemophilia-related hemarthroses. Splinting these patients may require that the plaster splint be placed only long enough to verify proper fit; the splint is then reapplied after setting (and cooling) of the plaster. If any patient complains of significant burning while the plaster is drying, do not ignore this complaint! Immediately remove the splint, and promptly cool the area with cold packs or cool water. Pressure Sores Pressure sores are an uncommon complication of short-term splinting. Attention to detail during padding and splinting reduces the incidence of pressure sores. However, whenever a patient complains of a persistent pain or burning sensation under any part of a splint, remove the splint and inspect the symptomatic area closely. The padding incorporated in premade plaster and fiberglass splints is generally all that is needed for safe short-term splinting. Many clinicians are unaware of the potential for drying plaster to produce seconddegree burns. The moist, warm, and dark environment created by the splint is an excellent nidus for infection. Toxic shock syndrome has been rarely reported from a staphylococcal skin infection that clandestinely developed under a splint or cast. In addition, it has been shown that bacteria can multiply in slowly drying plaster. To avoid infection, clean and débride all wounds before splint application, and use clean, fresh tap water for plaster wetting. If necessary, apply a removable splint that allows periodic wound inspection or local wound care. B, When immobilizing an infected human bite, this splint was not held in position until hardened, and the patient reflexively flexed the wrist. Patients, especially children, use various objects such as pencils, coat hangers, or forks to get to the itch.

Sinemet dosages: 300 mg, 125 mg, 110 mgSinemet packs: 30 pills, 60 pills, 90 pills, 120 pills, 180 pills, 270 pills, 360 pills

Leave the repair of lid avulsions treatment 4 anti-aging 110 mg sinemet purchase visa, extensive lid lacerations with loss of tissue, and complex types of lid lacerations to ophthalmologists. Ear Lacerations the primary goals in the management of lacerations of the pinna are expedient coverage of exposed cartilage and prevention of wound hematoma. Cartilage is an avascular tissue, and when ear cartilage is denuded of its protective, nutrient-providing skin, progressive erosive chondritis ensues. The first step in the repair of an ear injury is to trim away jagged or devitalized cartilage and skin. If the skin cannot be stretched to cover the defect, remove additional cartilage along the wound margin. Depending on the location, as much as 5 mm of cartilage can be removed without significant deformity. Approximate the cartilage with 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable sutures placed at folds or ridges in the pinna, representing major landmarks. Sutures tear through cartilage; therefore include the anterior and posterior perichondrium in the stitch. Next, in through-and-through ear lacerations, approximate the posterior skin surface with 5-0 nonabsorbable synthetic suture. Once closure of the posterior surface is completed, approximate the convoluted anterior surface of the ear with 5-0 or 6-0 nonabsorbable synthetic suture, joining landmarks point by point. In repair of the helical fold, use the inverting horizontal mattress stitch (see prior section in this chapter on mattress suture). Complex or complicated ear lacerations generally require consultation and close follow up. Nose Lacerations Lacerations involving the margin of the nostril are complicated and should be repaired accurately to ensure that unsightly notching does not occur. In the medial portion of the nostril and superior columella, the lower lateral cartilages are quite close to the margin and relatively superficial. If the extent of the laceration is not recognized or repaired, wound healing may cause superior retraction of the margin of the nostril. If bony deformity is noted, consider consulting a plastic surgeon, because the fragments may require surgical wiring. In repairing superficial lacerations of the nose, reapproximation of the edges of the wound is difficult because the skin is inflexible. Because it is difficult to approximate gaping wounds in this location, keep débridement to a minimum. Fortunately, the nose has a rich supply of blood and often will heal without débridement. Nasal cartilage is frequently involved in wounds of the nose, but it is seldom necessary to suture the cartilage itself. The inverting horizontal mattress stitch may be useful in the alar crease of the nostril to help with inversion (see prior section in this chapter on mattress suture). Many clinicians recommend early removal of stitches to avoid stitch marks, yet the oily nature of skin in this area makes it difficult to keep the wound closed with tape. A running subcuticular stitch may be preferable when repairing nasal lacerations, but simple interrupted stitches are also acceptable. This repair is best left to the ophthalmologist, but the emergency clinician must recognize the potential for a canaliculus injury. For fat to prolapse, the orbital septum (and potentially the globe itself) must have been perforated. Lip and Intraoral Lacerations Lip lacerations are cosmetically deforming injuries, but if the clinician follows a few guidelines, these lacerations usually heal satisfactorily. The contamination of all intraoral and lip wounds is considerable, and they must be thoroughly irrigated. Regional nerve blocks are preferred over local anesthetic injection because the latter method distends tissue, distorts the anatomy of the lip, and obscures the vermilion border.

Carum petroselinum (Parsley). Sinemet.

- Kidney stones, urinary tract infections (UTIs), cracked or chapped skin, bruises, tumors, insect bites, digestive problems, menstrual problems, liver disorders, asthma, cough, fluid retention and swelling (edema), and other conditions.

- Are there any interactions with medications?

- Dosing considerations for Parsley.

- How does Parsley work?

- What is Parsley?

- Are there safety concerns?

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96771

Cut the ends of the suture close to the knot to minimize the amount of suture material left in the wound medicine 5000 increase best 110 mg sinemet. Vessels smaller than 2 mm that bleed despite direct pressure can be controlled by pinpoint, bipolar electrocautery. A dry field is required for an effective electrical current to pass through the tissues. Minimize trauma by using fine-tipped electrodes to touch the vessel, or touch the active electrode of the electrocautery unit to a small hemostat or fine-tipped forceps while gripping the vessel. Keep the power of the unit to the minimum level required for thrombosis of the vessel. Self-contained, sterilizable, battery-powered coagulation units are alternatives to electrocautery. These devices cauterize vessels by the direct application of a heated wire filament. A cut vessel that retracts into the wall of the wound may frustrate attempts at clamping, ligation, or cauterization. Pass a suture through the tissue twice via a figure-of-eight or horizontal mattress stitch, and then tie it. They may bleed profusely, especially when the patient stands up and increases venous pressure. Place topical epinephrine (1: 100,000) on a moistened sponge and apply it to a wound to reduce the bleeding from small vessels. When combined with local anesthetics, such as lidocaine with epinephrine, concentrations of 1: 100,000 and 1: 200,000 prolong the effect of the anesthetic and provide some hemostasis in highly vascular areas. Hemostasis of a specific vessel may be achieved by directly injecting the soft tissues around the base of the bleeder with a small amount of lidocaine with epinephrine solution, even though the wound has previously been anesthetized. The combination of pressure and vasoconstriction may halt the bleeding long enough for the vessel to be ligated or cauterized, or to allow the wound to be closed and a compression dressing applied. Fibrin foam, gelatin foam, and microcrystalline collagen may be used as hemostatic agents. Their utility is limited in that vigorous bleeding will wash the agent away from the bleeding site. Their greatest value may be in packing small cavities from which there is constant oozing of blood. A tourniquet should first be used to minimize bleeding, and moisture should be dabbed away from the wound. This method is an off-label, anecdotal use of this product, and the consequence of exposing dermal skin layers directly to it have not been evaluated to date. In highly vascular areas such as the scalp, it is sometimes best to suture the laceration after exploration and irrigation of the wound despite active bleeding; the pressure exerted by the closure will usually stop the bleeding. If bleeding is too brisk to permit adequate wound evaluation and irrigation, control hemorrhage by clamping and everting the galea or dermis of each wound edge with hemostats. Raney clamps or a large hemostat is an excellent way to stop scalp bleeding; they are used during neurosurgical procedures. In the majority of simple wounds with persistent but minor capillary bleeding apposition of the wound edges with sutures, followed by a compression dressing, provides adequate hemostasis. Tourniquets If bleeding from an extremity wound is refractory to direct pressure, electrocauterization, or ligation, or if the patient has exsanguinating hemorrhage from the wound, place a tourniquet proximal to the wound to control the bleeding temporarily. Tourniquets are also helpful in examining extremity lacerations by providing a bloodless field. Although problems rarely develop from the use of tourniquets in routine wound care, potential problems can be minimized if (1) a limit is placed on the total amount of time that a tourniquet is applied, and (2) excessive tourniquet pressure is avoided. Another advantage of this technique is that contamination of the wound during closure is less likely. There is a real danger of forgetting to remove such a small tourniquet and accidentally incorporating it into the dressing. These techniques provide bloodless fields in which to examine, clean, and close extremity wounds. Débridement of questionably devitalized tissue in a wound is best accomplished without a tourniquet or pharmacologic vasoconstriction because bleeding from tissues is often an indication of their viability.

Syndromes

- Tremor

- When hiking in an area known to have snakes, wear long pants and boots if possible.

- Do NOT give the person salt tablets.

- Medicines that suppress the immune system, including chemotherapy and steroid medications

- Bleeding from eyes, ears, and nose

- Car beds

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) II

- Fatigue

- Exercise slows down the release of stress-related hormones. Stress increases the chance of illness.

- Sclerosing cholangitis

Other factors affecting transmucosal rectal absorption include the volume of liquid symptoms vaginal yeast infection sinemet 125 mg purchase with mastercard, concentration of the drug, length of the rectal catheter. Patients who refuse parenteral drug administration may also benefit from rectal delivery, as will those with nausea and vomiting or an inability to swallow. Rectal administration should be avoided in immunosuppressed patients, in whom even minimal trauma could lead to abscess formation, and in patients with severe thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy to avoid difficult-to-control bleeding. Finally, patients with a variety of acute or chronic anorectal problems such as fissures, hemorrhoids, or perianal abscesses or fistulas may not tolerate rectal drug administration. Anatomy and Physiology the rectum is the terminal portion of the large intestine; it begins at the confluence of the three taeniae coli of the sigmoid colon and ends at the anal canal. In adults, the anal canal is approximately 5 cm in length and the rectum is approximately 10 to 15 cm in length. For liquid and gel formulations, use an appropriately sized syringe attached to a small. The catheter is a thin silicone tube 14-Fr in diameter with a 15-mL balloon at the tip, sized to allow secure retention, yet also provide for ready elimination in the event of need for defecation. A 3-inch piece of tape placed across the buttocks also works well and frees the clinician to perform other duties. Procedure Suppositories Place adults and large children in a lateral recumbent position on the stretcher or examination table. Place the lubricated suppository at the rectal opening and gently push it into the rectum toward the umbilicus until the gloved index finger has been inserted approximately 7. To help prevent expulsion of the suppository, do not allow the patient to get up for approximately 10 to 15 minutes after insertion. Most suppositories have an apex at one end (pointed end) and taper to a blunt base at the other end. However, in 1991, Abd-El-Maeboud and colleagues found that inserting suppositories blunt end first resulted in greater retention within the rectum and a lower expulsion rate. The goal is to deposit the drug in the low to mid-portion of the rectum to avoid first-pass elimination by the liver. When administering rectal medication to infants and young children, be sure to squeeze the buttock cheeks closed after withdrawing the catheter to Medications A variety of medications can be administered rectally. In emergency medicine practice the most common medications given rectally are analgesics and antipyretics, sedative-hypnotic agents, anticonvulsants, antiemetics, and cation exchange resins. Analgesics and Antipyretics Acetaminophen is frequently administered rectally in children for both fever and pain. Common reasons for rectal administration include refusal to take the medication orally, vomiting, and altered mental status. Acetaminophen is commercially available in suppository form and is easy to obtain and administer. Studies comparing oral and rectal administration of acetaminophen have demonstrated equal antipyretic effectiveness. For example, aspirin is commonly administered rectally to adults with symptoms of a transient ischemic attack, an acute stroke, or an acute coronary syndrome who may have an impaired swallowing mechanism or are too unstable to take medication orally. Like acetaminophen, the oral and rectal doses of aspirin are similar (see Table 26. Rectal administration of methohexital and thiopental is particularly useful for non-painful procedures such as sedating children before advanced imaging studies. To prepare a solution of methohexital for rectal administration, add 5 mL of sterile water or saline to a 500-mg vial of methohexital and mix well; this provides a methohexital solution of 100 mg/mL. Diazepam is commercially available in a gel formulation that is preloaded in a rectal delivery system (Diastat AcuDial). The preloaded rectal delivery system is available for both pediatric and adult use. The adult device contains 4 mL (20 mg) of diazepam gel and has a 6-cm tip for rectal administration. The recommended dose of diazepam rectal gel for treating actively seizing children and those in status epilepticus is 0.

Usage: q.2h.

If time and effort have been invested in cosmetic closure of the face medicine 20th century purchase sinemet without prescription, protect the repair with skin tape after the skin sutures have been removed. With exposure to sunlight, scars in their first 4 months redden to a greater extent than the surrounding skin does. In exposed cosmetic areas and when prolonged exposure to the sun is anticipated, appropriate sun protection and avoidance strategies should be used. Sunscreen may have a role in protecting scars from the sun, but more studies are needed to better understand its impact. Some of the impediments to healing include ischemia or necrosis of tissue, hematoma formation, prolonged inflammation caused by foreign material, excessive tension on the edges of the skin, and immunocompromising systemic factors. Wound cleaning and débridement, atraumatic and aseptic handling of tissue, and the use of protective dressings minimize this complication. Inversion of the edges of a wound during closure produces a more noticeable scar, whereas skillful technique can convert a jagged, contaminated wound into a fine, inapparent scar. Delay in seeking treatment of an injury may significantly affect the ultimate outcome of the wound. Furthermore, in the first few days after an injury, the patient must take responsibility for protecting the wound from contamination, further trauma, and swelling. If the patient is careless or unlucky, reinjury can reopen a wound despite the protection of a thick dressing. A stitch that is too fine or tied too tightly may cut through friable tissue and pull out. If the wound edges show signs of separating at the time of suture removal, alternate stitches can be left in place and the entire length of the wound supported by strips of adhesive tape. Wounds located in sebaceous skin or oriented 90 degrees to dynamic or static skin tension lines result in wide scars. Wounds located in areas of high static skin tension will gape initially and often heal with wide scars despite adequate closure, whereas wounds in areas of loose or lax skin often heal with fine, narrow scars. For through-and-through punctures, the track can often be débrided by pulling gauze through the wound. It is impossible to accurately predict the final outcome of a puncture wound, though it may be determined at the time of the injury. No prospective randomized trials have evaluated the role of prophylactic antibiotic administration to prevent infection in puncture wounds. Hence there are no standards on the use, type, or duration of prophylactic antibiotic therapy, even in high-risk patients. Most clinicians forego routine antibiotics and opt for simple cleaning and appropriate follow-up. Puncture wounds of the bottom of the foot may be an exception and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 51. Studies by Ordog and colleagues91,92 documented a very low infection rate in gunshot wounds treated with standard wound care on an outpatient basis, even when the missile was left in place and minor fractures were present. Because most gunshot wounds are puncture wounds, only minimal deep wound cleaning is possible. Superficial soft tissue wounds with entrance and exit wounds in proximity may be débrided by passing sterile gauze back and forth through the wound track. Though prescribed frequently, no data support the routine use of antibiotics following gunshot wounds. Animal Bites Many aspects of the treatment of animal bites are controversial, and no universal standards exist. Numerous organisms can be cultured from an infected bite wound caused by a dog or cat, and cultures may guide antibiotic therapy in infected wounds. The predominant pathogens in animal bites are the oral flora of the biting animal and human skin flora. Approximately 85% of bites harbor potential pathogens, and the average wound yields five types of bacterial isolates; almost 60% have mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Pasteurella species are isolated from 50% of dog bite wounds and 75% of cat bite wounds. When compared with dog bites, cat bites may become infected rather quickly after the bite (within 24 hours), thus suggesting Pasteurella infection. Cat bite wounds tend to penetrate deeply, with a higher risk for osteomyelitis, tenosynovitis, and septic arthritis than with dog bites, which are associated with crush injury and wound trauma.

References

- Snell RE, Luchsinger PC: Determination of the external work and power of the intact left ventricle in intact man, Am Heart J 69:529-537, 1965.

- Robertson JH, Woodend BE, Crozier EH, Hutchinson J. Risk of cervical cancer associated with mild dyskaryosis. BMJ 1988; 297: 18-21.

- Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59(9):1207-13.

- Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al. Executive summary: the management of community acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society and the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53: 617-630.

- doi:10.1542/peds.2015-2982.

- Cohn JN, Tognoni G; Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2001;345:1667-75.

- Zeliadt SB, Moinpour CM, Blough DK, et al: Preliminary treatment considerations among men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer, Am J Manag Care 16:e121, 2010.

- Monet M, Domenga V, Lemaire B, et al. The archetypal R90C CADASIL-NOTCH3 mutation retains NOTCH3 function in vivo. Hum Mole Genet 2007;16(8):982-92.